Contemporary Church History Quarterly

Volume 19, Number 3 (September 2013)

Reflections on the Indian Residential Schools and the work of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada

By Steven Schroeder, University of the Fraser Valley

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (TRC) will convene in Vancouver, British Columbia for one week this month (18-21 September 2013) to hear survivors tell of their experiences in the Indian Residential Schools, and to encourage reconciliation between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples in Canada.[1] The work of the TRC has exposed weighty historical problems for all Canadians, but it has also provided Canadians opportunities to re-examine their country’s colonial policies, processes of nation-building and national identity formation, and its human rights record. For Christians, this work has evoked reason for critical reflection concerning mission work, evangelism, the role of the church in society, church-state relations, and how to best atone for past misdeeds.

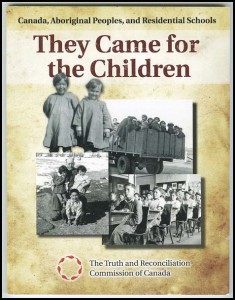

For over a hundred years (1880s-1996), the Canadian government partnered with the mainline churches — Roman Catholic, Anglican, Presbyterian, and United (and unofficially with Mennonite and Baptist organizations) – in running the Indian Residential School system. The 140 schools that comprised the system were found in every province and territory, even the northernmost regions of the Canadian arctic. The Indian Act, which mandated that Aboriginal children attend the schools, and court injunctions that threatened parents with arrest if they did not comply, ensured school enrollments.[2] In all, over 150,000 Aboriginal children – beginning at the age of six – were forcibly removed from their homes to attend state-sponsored, church-run schools. Hundreds of lawsuits stemming from abuses in the schools have led to numerous actions, including the establishment of the TRC. The first task of the TRC was to establish and disseminate the facts regarding the school system. The 2012 book They Came for the Children: Canada, Aboriginal Peoples, and Residential Schools is a product of the commission’s work.

The book explains how the churches in Canada began their missionary work of converting Aboriginals to Christianity and to western cultural practices long before confederation. This foundation proved useful to Canadian government officials who found accord with the church leaders’ intent “to civilize and Christianize” Aboriginal children.[3] Together, the government and the churches expanded the existing church education infrastructure to all of Canada with the intent to, as government officials put it, “kill the Indian in the child.” The campaign to eliminate Canada’s “Indian problem” was to be achieved through assimilation, extinguishing Aboriginal culture, and eliminating Aboriginal interest in land claims. Although Canada’s population would be multi-racial, the success of the assimilation campaign would ensure that all Canadians were sufficiently “civilized” (i.e., westernized and Christian), thereby reducing the government’s treaty obligations considerably.[4]

The book explains how the churches in Canada began their missionary work of converting Aboriginals to Christianity and to western cultural practices long before confederation. This foundation proved useful to Canadian government officials who found accord with the church leaders’ intent “to civilize and Christianize” Aboriginal children.[3] Together, the government and the churches expanded the existing church education infrastructure to all of Canada with the intent to, as government officials put it, “kill the Indian in the child.” The campaign to eliminate Canada’s “Indian problem” was to be achieved through assimilation, extinguishing Aboriginal culture, and eliminating Aboriginal interest in land claims. Although Canada’s population would be multi-racial, the success of the assimilation campaign would ensure that all Canadians were sufficiently “civilized” (i.e., westernized and Christian), thereby reducing the government’s treaty obligations considerably.[4]

The horrible accounts in the book reveal terrible abuses that the vast majority of these students experienced in the dysfunctional, ill-planned, and under-funded school system. Students were abused emotionally, physically, and sexually, and they were punished for using their language.[5] Tuberculosis and other serious illnesses were rampant, and the death rate was very high (at school, and after release). For instance, during the first decade of operations at the residential school at Qu’Appelle, 174 of 344 students died from a variety of illnesses.[6] Funding was woefully inadequate, leaving students undernourished and tasked with all sorts of labour jobs, thus sidelining school work. The utter failure of the residential school system was obvious to all by the early 1900s, and many people – even some government officials – supported closing the schools decades prior to their actual closure.[7]

The history of the residential schools has only partly been realized by the Aboriginal community, and has been almost entirely unknown to the non-Indigenous population in Canada. It seems that the churches and the government intended for the abuses of the failed campaign to fade away with the schools themselves. However, the Canadian Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples’ 1996 report documented the suffering of the students in the residential schools, which gave rise to hundreds of legal claims aimed at the churches and the federal government. The resulting 2007 Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement totaled $1.9 billion, $60 million of which was designated for the establishment and activities of the TRC.

The mandate of the TRC – to find facts and foster reconciliation – has been frustrated from the outset of its mission due to the Canadian government’s refusal to open its archives to the commission’s researchers (They Came for the Children is based mostly on published materials).[8] Even though Prime Minister Stephen Harper gave a formal apology on behalf of the Canadian government in 2008, one has to wonder about what the apology actually addressed, and what remains overlooked. Withholding the documents has added to past indignities, deepened the distrust between Canadians and their government, and limited the scope of reconciliatory work. In response, Aboriginal writer Leanne Betasamosake Simpson recently called on the Canadian government to: “Honour the apology. Release the documents. Be on the right side of history on this one. It’s the very, very least you can do.”[9]

The government’s resistance to full cooperation with the TRC has not kept other researchers from finding new information on human rights violations in the residential schools. Recent research by food historian Ian Mosby has revealed that Canadian nutritionists partnered with government agencies and church personnel in conducting nutritional and pharmaceutical experiments on malnourished Aboriginal children in six residential schools.[10] Food rations were kept low intentionally, and any useful findings were to benefit non-Indigenous Canadians (which they did). One wonders about what other accounts exist in the archival documents that have remained under lock and key, but it appears that we may soon find out. An Ontario court injunction of January 2013 forced the hand of the government, and in August 2013 the first researchers from the TRC gained access to the federal government’s records of the residential schools. The research team now finds itself on a tight schedule, as the TRC’s mandate expires in mid-2014.

The residential school system is truly Canada’s national shame. At stake is the integrity of the government, the churches, and the very fabric of Canadian society. The government’s lack of cooperation in the fact-finding stage of the TRC’s work has impeded reconciliation. How can Canadians address their past appropriately, when they don’t know the facts? Without the facts, how can all Canadians work together toward a better future? Head of the TRC, Chief Wilton Littlechild, has rightly claimed: “People just don’t know the history [of the residential schools], and once they know the history, they’ll make the connection as to why there is such a high rate of addiction, and why there is such a high rate of suicide and unemployment [in some Aboriginal communities].”[11] Also at stake is the integrity of the churches. Some Christian pacifists in Canada who claimed Conscientious Objector status during the Second World War, satisfied their alternative service requirement by joining the teaching staff in the racist, abusive residential schools. This, and related accounts of Christian reasoning for complicity in the school system brings into question aspects of Christian pacifism, Christian missions, evangelism, the role of the church in society and nation building, and the relationship between church and state. Some Christians have begun to address these issues positively, and in new ways. During 1991-1998, all of the churches involved in the schools issued formal apologies for their respective roles in the schools, and the churches have continued to work toward reconciliation with Indigenous peoples.[12] These efforts will be encouraged at the TRC events in Vancouver, where one will find church tents for conversation, healing, and reconciliation.

Even if Aboriginal survivors of the residential school system were left to initiate the processes of reconciliation through airing grievances, lawsuits, and court injunctions, the results of these actions have been promising. With the TRC publicly revealing these facts and raising awareness among Canadians, Canadians now have the opportunity to respond, and to act in keeping with their long, proud history of being “peacekeepers.” There is plenty of peacebuilding work to be done within their own communities, between peoples of diverse backgrounds, cultures, and worldviews. To date, the response in Canadian cities to the work of the TRC has been mostly positive, evident in thousands of people attending the TRC events, including walks for reconciliation. It would appear that the public is on board.[13] Sustaining and growing this interest among Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples in Canada is crucial to moving forward the reconciliatory work that is already underway.

Notes:

[1] For information on the Vancouver Truth and Reconciliation Commission events in September 2013, see: http://www.myrobust.com/websites/vancouver/index.php?p=719#. For events at universities in the Vancouver area, see: University of the Fraser Valley: http://www.ufv.ca/indigenous/day-of-learning/ University of British Columbia: http://irsi.aboriginal.ubc.ca/ Simon Fraser University: http://www.sfu.ca/reconciliation.html

[2] Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, They Came for the Children: Canada, Aboriginal Peoples, and Residential Schools. (Winnipeg: TRC, 2012), 18.

[3] TRC, They Came for the Children, 10.

[4] TRC, They Came for the Children, 6.

[5] TRC, They Came for the Children, 1,2,10,37-45

[6] TRC, They Came for the Children, 17

[7] TRC, They Came for the Children, 17, 19.

[8] Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, Interim Report (Winnipeg: TRC, 2012), 15-16.

[9] Leanne Betasamosake Simpson, “Honour the Apology,” blog entry (23 July 2013): http://leannesimpson.ca/2013/07/23/honour-the-apology/#more-866 (p.3)

[10] See Ian Mosby, “Administering Colonial Science: Nutrition Research and Human Biomedical Experimentation in Aboriginal Communities and Residential Schools, 1942-1952,” Food Deprivation and Aboriginals,” Histoire sociale/Social History, vol. XLVI, 91 (Mai/May 2013): 145-172

[11] Jamie Ross, “Littlechild: Commission will uncover the truth – Residential schools: Head of commission says system tore apart families,” May 30th, 2011 http://media.knet.ca/node/11250

[12] See TRC, They Came for the Children, 81. Official apologies regarding the Residential Schools were as follows: Roman Catholic Oblate (1991), Anglican Church of Canada (1993), Presbyterian Church of Canada (1994), and United Church of Canada (1998). For publications and websites, see: The United Church of Canada, Justice and Reconciliation: The Legacy of Indian Residential Schools and the Journey Toward Reconciliation. (United Church: 2001); Jeremy Bergen, Ecclesial Repentance: The Churches Confront their Sinful Pasts. (Continuum: 2011); Mennonite websites: http://bc.mcc.org/whatwedo/TRC; http://mcbc.ca/trc-2013/ ; Anglican website: http://www.anglican.ca/relationships/trc ; Presbyterian website: http://presbyterian.ca/healing/more/; Roman Catholic website: http://www.cccb.ca/site/eng/media-room/archives/media-releases/2008/2590-launching-of-truth-and-reconciliation-commission-an-opportunity-for-healing-and-hope

[13] Environics Research Group, 2008 National Benchmark Survey, Indian Residential Schools Resolution Canada

and the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, 2008. This survey revealed that “Fully two-thirds (67%) of Canadians believe that individual Canadians have a role to play in efforts to bring about reconciliation in response to the legacy of the Indian residential schools system, even if they had no experience with Indian residential schools.” (29)